A terrific Kirsten Dunst plays a jaded photojournalist documenting the end of democracy as we know it in what’s sure to be one of the year’s most controversial films.

Courtesy of SXSW

The press are the good guys, but also kind of the bad guys, in Alex Garland’s virtuosic “Civil War,” a jarring ground-level account of what a near-future disunification of the United States might look like. Intended as a wake-up call, the long-fuse thriller — which starts slow and snowballs to a jaw-dropping raid on Washington, D.C. — embeds viewers alongside a dedicated team of journalists making their way to the Capitol while the country unravels around them.

It’s the most upsetting dystopian vision yet from the sci-fi brain that killed off all of London for the zombie uprising depicted in “28 Days Later,” and one that can’t be easily consumed as entertainment. A provocative shock to the system, “Civil War” is designed to be divisive. Ironically, it’s also meant to bring folks together.

Led by veteran war photographer Lee Smith (Kirsten Dunst), the tight crew of journalists are total pros. They represent a troubling form of detachment, essential to their job yet practically counter-human as they endeavor not to take sides, which serves as an indictment unto itself.

News outlets thrive on conflict, which sells papers and drives ratings, going so far as to foment fear around the possibility of a second American civil war. Garland doesn’t care how this one happened. His script skips past why the conflict started, offering only the questionable notion that Texas and California both seceded and subsequently pooled resources (calling themselves “the Western Forces”) against a power-hungry three-term president (Nick Offerman).

Though it looks like another entry in the popular post-apocalyptic thriller genre, make no mistake: “Civil War” depicts the apocalypse itself. The country’s in full meltdown, suggested more than depicted outright. Americans have turned on one another, and the only people permitted to move freely through active-fire spaces are the ones with “PRESS” stenciled on their flak jackets.

Garland establishes the chaos early, as Lee covers a mob scene where civilians reduced to refugees in their own country clamor for water. Suddenly, a woman runs in waving an American flag, a backpack full of explosives strapped to her chest.

Like the coffee-shop explosion in Alfonso Cuarón’s “Children of Men,” the vérité-style blast puts us on edge — though the wider world might never witness it, were it not for Lee, who picks up her camera and starts documenting the carnage. Seconds before, she’d pulled a young admirer, Jessie (“Priscilla” star Cailee Spaeny), to safety, effectively saving the life of this wet-behind-the-ears wannabe.

It’s Jessie goal to be a war photographer, though she works with black-and-white film — a young artiste to Lee’s run-and-gun shooter. The ambitious newcomer talks her way into Lee’s next mission, driving with reporter Joel (Walter Moura) and veteran political journalist Sammy (Stephen McKinley Henderson) to D.C. to interview the president — three generations of journos with very different agendas.

Jessie sees herself in the girl, even if she doesn’t see herself in her own reflection anymore. In a quiet but revealing scene, the foursome roll into a town that seems untouched by war. They step into a shop, where Lee tries on a dress, studying herself in the mirror.

The movie is that mirror, showing America the risks of in-fighting and the potential costs of division. “Civil War” is a cautionary tale, repurposing the sort of imagery audiences have seen in overseas war zones — dissidents hanging from bridges, lime-covered corpses piled into mass graves — and applying them to familiar, all-American settings.

It’s startling, to say the least. Still, Lee has seen worse in her life (early on, decompressing in her bath, she cycles through a sampling of arm’s-length horrors she’s documented over her career, including a man lit on fire).

If ever she knew empathy, Lee now seems desensitized beyond repair. When Jessie asks her idol what she’d do if Jessie were dying, Lee stares back coldly and says, “What do you think?” She’d get the shot, of course.

Audiences have never seen Dunst like this. She looked rough in “Power of the Dog,” but here, covering conflicts has drained the essence right out of her. (The star appeared radiant at the film’s SXSW premiere, underscoring the transformation she undertook for a role where resilience and plain, adrenaline-fueled instinct override basic self-care.)

Garland gives the character several opportunities to reconnect with her humanity, even as this tense, increasingly brutal road trip pushes the team deeper into the proverbial heart of darkness. Most of the movie takes place in broad daylight, not at all the aesthetic audiences expect from a modern-day war movie, which typically uses strategic filters to make everything look gritty.

“Civil War” may unfold in a parallel dimension (the Cal-Texan team-up blurs whether blue or red states are running this uprising), but it looks a lot like the America we know. At times, amid the confusion, the characters can’t distinguish between rebels and patriots — as in a scene at an outdoor Winter Wonderland attraction, where soldiers try to take out a sniper.

In that situation, it hardly matters which team he’s on. Later, Jessie Plemons shows up wearing a camo uniform and heart-shaped sunglasses, pointing his gun at the unarmed journalists. “What kind of American are you?” he demands of each of them. In today’s political climate, some pose similar questions, with equally intimidating subtext.

By this point, the film has tilted toward full-blown horror. Indeed, the final stretch feels more like something out of Stephen King (“The Mist” or “The Stand”) than any war movie that’s come before, as the small band of journalists accompanies the Western Forces for its big push on D.C.

Although Garland showed Offerman preparing a speech as president at the outset, he seeded doubts in the man’s sincerity by intercutting real-world uprisings with the commander in chief’s words. Even so, surely no American wants to see what comes next, as Jessie and Lee shadow troops trying to shoot their way into the White House.

Earlier, the battles were intense but somehow theoretical. This climactic siege looks terrifying, albeit wildly different from the kind of real-world warfare witnessed in Ukraine. At first, Jessie tended to freeze up under fire, but now she appears fearless, while Lee is racked by anxiety attacks. If you saw combat boots stomping the American flag, could you stand by and take pictures?

Sick to her soul, Lee’s reaction feels practically out of character, as the sight of democracy being overturned stops her cold. But only for a moment. Embedded alongside insurrectionists whom the media may well have inspired, these eyewitnesses to history are fueled by a totally distorted sense of duty: Their sole focus is to get the shot — or the story, as the case may be.

Anyone who saw Garland’s previous film, the A24-backed freakout “Men,” knows the director doesn’t shy away from pushing things to their most nauseating extreme. “Civil War” is no different.

Garland trades in triggering images, not just of war crimes of the image-makers themselves, far from neutral, all but encouraging acts that make Jan. 6 look mild. Meanwhile, ambiguities surrounding the origins of the conflict mean there’s no way to defuse what we’re watching.

Sight unseen, “Civil War” has been criticized for exploiting tensions in an election year, when in fact, it’s meant to illustrate the futility of “sides.” Garland’s the last person to suggest a group hug. As statements go, his powerful vision leaves us shaken, effectively repeating the question that quelled the L.A. riots: Can we all get along?

News

ENGLAND fans at home and in Germany are gearing up for the Three Lions’ crunch Euros quarter-final with Switzerland – with kick-off less than an hour away.

ENGLAND fans at home and in Germany are gearing up for the Three Lions’ crunch Euros quarter-final with Switzerland – with kick-off less than an hour away. Supporters are packing out the streets of Dusseldorf ahead of this afternoon’s knock-out game….

Mike Tyson Warns Jake Paul: “HIDE WELL, DON’T LET ME CATCH YOU”

In a recent statement that has sent shockwaves through the boxing world, legendary fighter Mike Tyson issued a stark warning to Jake Paul ahead of their anticipated showdown. Tyson, known for his intimidating presence and formidable boxing skills, didn’t mince…

Logan Paul INSTRUCTS Jake Paul On How To Evade Mike Tyson’s Punches DROP HIS PANTS And RUN As Fast As

In a recent YouTube video, Logan Paul shared some shockingly candid advice for his younger brother Jake Paul on how to handle an encounter with boxing legend Mike Tyson. According to Logan, the best way for Jake to dodge Tyson’s…

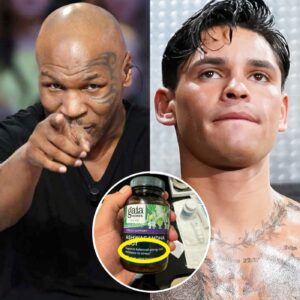

(+VIDEO)Mike Tyson BRUTALLY HONEST On Ryan Garcia Failed DR*G Test Against Devin Haney

In an explosive revelation that has the sports world reeling, boxing legend Mike Tyson has openly criticized the handling of Ryan Garcia’s failed drug test prior to his highly anticipated bout against Devin Haney. The incident, which has cast a…

Coach Mike Tyson Shares CONFIDENTLY When Predicting That Mike Will ‘KO In Round 1’ Against Jake Paul In An ONLINE INTERVIEW With Piers Morgan

In a riveting online interview with Piers Morgan, Coach Mike Tyson exudes unwavering confidence as he forecasts a swift victory for boxing legend Mike Tyson in his upcoming bout against Jake Paul. The anticipation surrounding this highly anticipated match has…

Conor Mcgregor And His Trainer Make A SURPRISING STATEMENT About The Fight Between Mike Tyson And JakeA Paul And The Issue Surrounding Fight Watchers

In a recent turn of events, Conor McGregor and his renowned trainer have stirred up the boxing world with their unexpected commentary on the much-anticipated showdown between boxing legend Mike Tyson and the polarizing YouTube sensation turned boxer, Jake Paul….

End of content

No more pages to load